Executive Summary

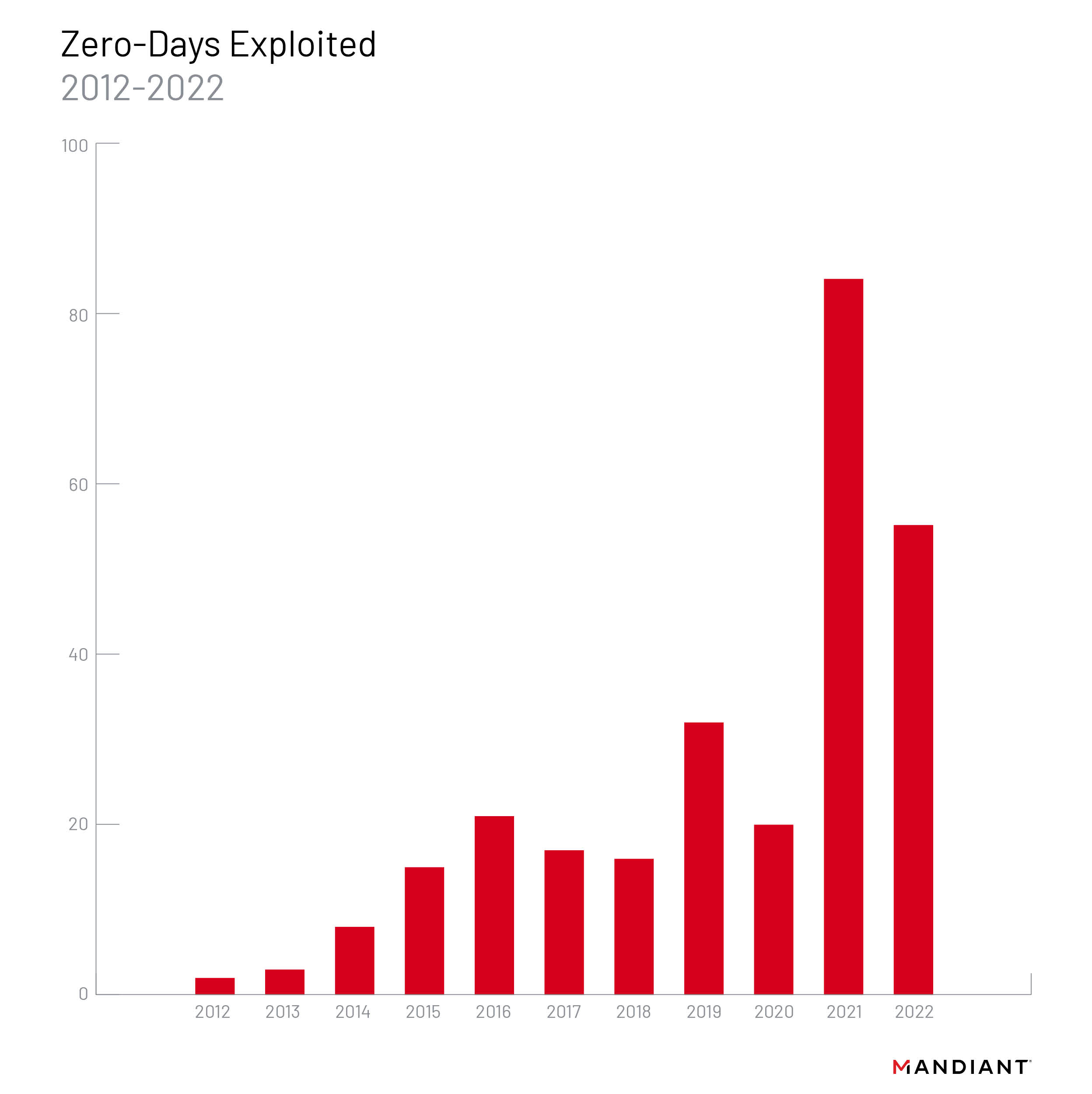

- Mandiant tracked 55 zero-day vulnerabilities that we judge were exploited in 2022. Although this count is lower than the record-breaking 81 zero-days exploited in 2021, it still represents almost triple the number from 2020.

- Chinese state-sponsored cyber espionage groups exploited more zero-days than other cyber espionage actors in 2022, which is consistent with previous years.

- We identified four zero-day vulnerabilities exploited by financially motivated threat actors. 75% of these instances appear to be linked to ransomware operations.

- Products from Microsoft, Google, and Apple made up the majority of zero-day vulnerabilities in 2022, consistent with previous years. The most exploited product types were operating systems (OS) (19), followed by browsers (11), security, IT, and network management products (10), and mobile OS (6).

Scope

The purpose of this report is to share insights from Mandiant’s analysis of 2022 zero-day exploitation. Mandiant considers a zero-day to be a vulnerability that was exploited in the wild before a patch was made publicly available. This report examines zero-day exploitation identified in Mandiant’s original research, combined with breach investigation findings, and reporting from open sources, focusing on zero-days exploited by named groups. While we believe the referenced open sources are reliable as used in this analysis, we cannot independently confirm the findings of some sources. Technical details of the vulnerabilities are not included; rather, we discuss overall takeaways from threat actor activity, vulnerability trends, and targeted vendors and products. Due to the ongoing discovery of past incidents through digital forensic investigations, we expect that this research will remain dynamic and may be supplemented in the future.

Overall Count

Mandiant tracked 55 zero-day vulnerabilities that we judge were exploited in 2022. While this count is 26 fewer than the record-breaking 81 zero-days exploited in 2021, it was still significantly higher than in 2020 and years prior (Figure 1).

We previously predicted that zero-day vulnerabilities would continue to be exploited at a significantly higher rate than in the 2010s, and the 55 zero-days identified this year indicate a continuation of that trend. A number of factors may have contributed to the zero-day count in 2020 dipping, then quadrupling in 2021. Pandemic related disruptions in 2020 potentially interrupted reporting and disclosure workflows for vendors, reduced capacity for defenders to detect exploitation activity and, may have encouraged attackers to reserve novel exploits except in the most important cases. Moreover, in 2021 Apple and Android disclosures included more exploitation information.

We anticipate that the longer term trendline for zero-day exploitation will continue to rise, with some fluctuation from year to year. Attackers seek stealth and ease of exploitation, both of which zero-days can provide. While the discovery of zero-day vulnerabilities is a resource-intensive endeavor and successful exploitation is not guaranteed, the total number of vulnerabilities disclosed and exploited has continued to grow, the types of targeted software, including Internet of Things (IoT) devices and cloud solutions, continue to evolve, and the variety of actors exploiting them has expanded.

State-Sponsored Groups Continue to Drive Exploitation

We tracked 13 zero-days in 2022 that we assess with moderate to high confidence were exploited by cyber espionage groups. Consistent with previous years, Chinese state-sponsored groups continue to lead exploitation of zero-day vulnerabilities with seven zero-days exploited or over 50% of all zero-days we could confidently link to known cyber espionage actors or motivations. Notably, at a slightly elevated rate compared to previous years, we identified two zero-day vulnerabilities that were exploited by suspected North Korean actors.

We identified four zero-day vulnerabilities for which we could attribute exploitation by financially motivated threat actors, a quarter of the total 16 zero-days for which we could determine a motivation for exploitation. 75% of these instances appear to be linked to ransomware operations, consistent with 2021 and 2019 data in which ransomware groups exploited the highest volume of zero-day vulnerabilities compared to other financially motivated actors. However, the overall count and proportion of the total of financially motivated zero-day exploitation declined in 2022 compared to recent years.

Oops They Did It Again: Chinese Threat Groups Lead Zero-Day Exploitation

Mandiant and open sources attributed 13 zero-days exploited in 2022 to likely state-sponsored groups, representing over 80% of the total for which we could identify the motivation of the actors.

China

In 2022, Chinese espionage groups exploited seven zero-day vulnerabilities, more than we were able to attribute to any other state sponsor. Compared to the watershed year in 2021 in which Chinese state-sponsored threat groups exploited at least eight separate zero-days, Chinese exploitation slightly decreased in 2022. Three campaigns in 2022 were particularly notable due to the involvement of multiple groups, expansive targeting, and focus on enterprise networking and security devices: multiple groups exploiting CVE-2022-30190 (aka Follina) in early 2022, and the 2022 exploitation of FortiOS vulnerabilities CVE-2022-42475 and CVE-2022-41328.

China Continues to Focus on Network Devices

In late 2022, we observed a suspected Chinese state-sponsored threat group exploit CVE-2022-42475, a vulnerability in Fortinet’s FortiOS SSL-VPN. We have some evidence to suggest the exploitation began as early as October 2022 based on netflow data that revealed interest in a European government entity and a managed service provider located in Africa. This activity continues China’s pattern of exploiting internet-facing devices, especially those used for managed security purposes (e.g., firewalls, IPS/IDS appliances etc.). We anticipate this tactic will continue to be the intrusion vector of choice for well-resourced Chinese groups.

- During our investigation of this activity, we identified a new malware tracked as “BOLDMOVE.” We uncovered both a Windows and a Linux variant of BOLDMOVE, which is specifically designed to run on FortiGate Firewalls. With BOLDMOVE, the attackers not only developed an exploit, but malware that shows an in-depth understanding of systems, services, logging, and undocumented proprietary formats.

In mid-2022, Mandiant investigated the exploitation and deployment of malware across multiple Fortinet solutions, activity which we attribute to UNC3886. With initial access to a publicly exposed FortiManager device, UNC3886 exploited a directory traversal zero-day vulnerability in FortiOS (CVE-2022-41328) to write files to FortiGate firewall disks outside of the normal bounds allowed with shell access. UNC3886 is a suspected Chinese cyber espionage group to which we also attributed the novel VMware ESXi hypervisor malware framework disclosed in September 2022.

A Digital Quartermaster?

As early as March 2022, Mandiant identified suspected Chinese activity exploiting CVE-2022-30190 (aka Follina) in Microsoft Diagnostics Tool (MDST) that would allow an attacker to execute arbitrary code. The vulnerability is exploited primarily through convincing users to open Word documents; it can also be exploited through other vectors that process URLs. We observed at least three separate activity sets exploit Follina as a zero-day in support of operations against public and private organizations in three distinct regions. Multiple separate campaigns may indicate that the zero-day was distributed to multiple suspected Chinese espionage clusters via a digital quartermaster.

- Mandiant identified an activity cluster tracked as UNC3658 leverage samples exploiting CVE-2022-30190 likely targeting the Philippine Government from March to May 2022.

- In April 2022, we observed two additional samples exploiting CVE-2022-30190 that appeared to have been leveraged against telecommunications and business service providers in South Asia. We track this activity as UNC3347.

- We identified a third cluster, UNC3819, likely exploiting CVE-2022-30190 against organizations in Belarus and Russia in May 2022. At least two samples used lure content related to the war in Ukraine.

Mandiant noted previous waves of the progressive adoption of the same exploit among Chinese espionage groups prior to the release of a public patch (e.g., the widespread “ProxyLogon” campaign in early 2021) which potentially indicates the existence of a shared development and logistics infrastructure and possibly a centralized coordinating entity. Mandiant research dating back to 2013 has likewise suggested a logistical support function or quartermaster supporting Chinese cyber espionage groups.

North Korea

Notably, at a slightly elevated rate compared to previous years, we identified two zero-day vulnerabilities that were exploited by North Korean actors, including some operations that overlap with TEMP.Hermit whose activities are reported as “Operation Dream Job” or Operation AppleJeus by Google TAG. These clusters reportedly used the same exploit kit to exploit Google Chrome zero-day CVE-2022-0609 in February 2022 to target the media, high-tech, and financial sectors. In November 2022, Mandiant identified a tracked cluster of activity that had targeted the high-tech sector in South Korea with spear-phishing emails containing malicious attachments exploiting CVE-2022-41128, a zero-day vulnerability in Microsoft Windows Server. Indicators associated with this phishing activity are consistent with what TAG reported and tracks as APT37, but we are unable to confirm if this cluster is tied to APT37 at this time.

Russia

We observed two instances of Russian state zero-day exploitation, when APT28 exploited CVE-2022-30190 (aka Follina) in early June 2022, and the months-long campaign exploiting Microsoft Exchange vulnerability CVE-2023-23397, activity which Mandiant tracks as UNC4697 and which open sources have attributed to APT28. The campaign exploiting CVE-2023-23397 has been ongoing since at least April 2022 and targeted government, logistics, oil/gas, defense, and transportation industries located in Poland, Ukraine, Romania, and Turkey. The increased focus on disrupting Russian cyber operations since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may have discouraged Russian operators from widely using valuable zero-day exploits for access they expected to lose quickly. While exploitation of CVE-2022-30190 (aka Follina) was likely opportunistic, taking advantage of the gap between disclosure and patch release, the use of CVE-2023-23397 suggests that the operators perceived the targets of this campaign to be of high intelligence value. Based on our research, Russian threat actors have exploited two zero-days per year since 2019, with the trend continuing into 2022.

Commercial Vendors

Commercial vendors again made headlines in 2022 during which tool suites or exploitation frameworks utilized by their customers accounted for three zero-days, or approximately one quarter of all vulnerabilities attributed to state-sponsored espionage activity. Despite recent struggles of some high-profile vendors, we assess with moderate confidence that there continues to be a very active and vibrant market for third-party malware, particularly surveillance tools, across the globe. Multiple Western nations have moved to restrict domestic companies and ex-government employees from some participation in these activities; however, there is a significant base of expertise outside the countries moving to restrict vendors of these capabilities. As a result, we judge that these restrictions will only have a limited effect on the overall market.

We observed at least three separate zero-day vulnerabilities exploited in 2022 by tools, suites, or exploitation frameworks developed by at least three distinct commercial vendors.

- Consistent with previous activity, Candiru reportedly exploited one zero-day (CVE-2022-2294) targeting Google’s Chrome browser in 2022.

- According to open sources, the Candiru-developed Chrome zero-day was used in an operation that compromised a website used by employees of a news agency, which is consistent with the use of previous Candiru exploits to target journalists, and it primarily affected users located in the Middle East.

- Two European malware vendors also reportedly exploited one zero-day vulnerability each: Variston, identified by Google TAG targeting Mozilla’s Firefox browser (CVE-2022-26485), and DSIRF, which targeted Microsoft Windows Server (CVE-2022-22047).

- DSIRF’s zero-day exploit was reportedly leveraged to target law firms, banks, and strategic consultancies in countries including Austria, the United Kingdom, and Panama.

Financially Motivated Exploitation Less Prominent in 2022

Though the proportion of zero-days exploited in financially motivated operations declined in 2022, n-day vulnerability exploitation, the exploitation of vulnerabilities that have already received patches, remains one of the most frequently observed initial infection vectors in Mandiant Incident Response and Managed Defense investigations of ransomware and/or extortion incidents. In 2022, we identified four zero-day vulnerabilities as likely exploited in financially motivated operations, mostly linked to ransomware activity.

- In one instance, an actor who ultimately deployed Lorenz ransomware reportedly went out of the way to avoid detection while exploiting a novel remote code execution (RCE) flaw on Mitel’s MiVoice Connect VOIP appliance (CVE-2022-29499).

- Open sources indicated that the Magniber ransomware group exploited CVE-2022-41091, a vulnerability in the Mark of the Web (MoTW) feature in Microsoft Windows 11, as a zero-day in September 2022. Separately, open sources reported that the Magniber group also exploited CVE-2022-44698, a different MoTW vulnerability, in October 2022, before the vulnerability was patched by Microsoft in December.

- We observed UNC2633, a distribution threat cluster that delivers emails containing malicious attachments or links that lead to malware payloads, exploit CVE-2022-30190 (aka Follina) in at least three instances in early June 2022 before the patch was released. In at least two of those instances, UNC2633 used the zero-day vulnerability to distribute QAKBOT on the victims’ networks.

There are multiple factors that may have contributed to this decline. 2021 was an exceptional year for zero day exploitation across the board, and at least one significant campaign associated with extortion operations utilized four Accellion FTA vulnerabilities together. Some of the most prolific ransomware groups that exploited zero-days in previous years had operators based in Russia or Ukraine, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 may have disrupted this criminal ecosystem and contributed to a decline in zero-day use. The overall decline in ransomware payments in 2022 may have also reduced the capacity of operators to acquire or develop zero-days.

You. Will. Be. Popular.

Zero-Days Exploited by Vendor

The technologies most frequently affected by zero-days in 2022 reflect a similar distribution as years prior and again overwhelmingly focus on the three largest vendors whose technology is widely adopted across the world. Microsoft (18), Google (10), and Apple (9) were the most commonly exploited vendors for the third year in a row.

We judge that threat actors most often pursue zero-day vulnerabilities in such ubiquitous products due to the wide access that exploitation of these products can provide. We also observed more unique vendors or niche products that were targeted, which may indicate a focus by some threat actors on those systems based on specific targets or victims of interest, and those technologies being a particularly useful attack vector in those specific cases.

Zero-Days Exploited by Product Type

The most exploited products were operating systems (OS) (19); followed by browsers (11); security, IT, and network management products (10); and mobile OS (6).

- Desktop operating system exploitation continues to primarily affect Windows, with 15 zero-days exploiting this product in 2022. In comparison, macOS was exploited in only four out of 19 identified OS zero-days.

- Browser exploitation saw an even higher bias toward its top target, Chrome, with 9 out of 11 browser zero-day vulnerabilities, compared to Firefox’s two. This trend reinforces our judgment that popular technologies are the most desirable targets to threat actors since Chrome is the browser choice of the majority of web users, estimated at about 60–65% use globally.

- Ten zero-day vulnerabilities, nearly 20% of all zero-days we identified in 2022, affected security, IT, and network management products (Table 1).

Mobile Operating Systems

We tracked six mobile OS zero-day vulnerabilities as exploited in 2022. Given that global OS market shares are increasingly composed of mobile OS, we anticipate that vulnerabilities affecting mobile devices will continue to rise compared to other categories. However, desktop technologies likely will remain of interest to threat actors given their role in enterprise networks and access to critical data. Threat actors targeting a specific person may be more likely to seek mobile OS exploitation, while attackers targeting organizations may seek desktop or other frequent enterprise technologies.

Gaining an Edge, on the Edge

Threat actors, particularly those seeking to remain undetected, likely target security, network, and IT management or “edge infrastructure” products because they are always internet-facing and often do not host E/XDR or detection solutions. Threat actors may gain an edge against defenders by not moving within heavily monitored areas of targeted infrastructure.

These devices are attractive targets for multiple reasons. First, they are accessible to the internet, and if the attacker has an exploit, they can gain access to a network without requiring any victim interaction. This allows the attacker to control the timing of the operation and can decrease the chances of detection. Malware running on an internet-connected device can also enable lateral movement further into a network and enable command and control by tunneling commands in and data out of a network.

It is important to note that many of these types of products do not offer a simple mechanism to view which processes are running on the device’s operating systems. These products are often intended to inspect network traffic, searching for anomalies as well as signs of malicious behavior, but they are often not inherently protected themselves.

|

2022 Security, IT, and Network Management Zero-Day Vulnerabilities |

|

|

CVE |

Product |

|

CVE-2022-1040 |

Sophos Firewall |

|

CVE-2022-3236 |

Sophos Firewall |

|

CVE-2022-20821 |

Cisco IOS |

|

CVE-2022-26871 |

Trend Micro Apex Central |

|

CVE-2022-40139 |

Trend Micro Apex One |

|

CVE-2021-35247 |

SolarWinds Serv-u |

|

CVE-2022-28810 |

Zoho ManageEngine |

|

CVE-2022-27518 |

Application Delivery and Load Balancer |

|

CVE-2022-42475 |

Fortinet FortiOS |

|

CVE-2022-41328 |

Fortinet FortiOS |

Exploitation Consequences

Almost all 2022 zero-day vulnerabilities (53) were exploited for the purpose of achieving either (primarily remote) code execution or gaining elevated privileges, both of which are consistent with most threat actor objectives. While information disclosure vulnerabilities can often gain attention due to customer and user data being at risk of disclosure and misuse, the extent of attacker actions from these vulnerabilities is often limited. Alternatively, elevated privileges and code execution can lead to lateral movement across networks, causing effects beyond the initial access vector.

Don’t You Forget About Me: Undue Focus on New Vulnerabilities Can Fatigue Defenders

Although uncommon, vulnerabilities may be publicly disclosed with workaround guidance instead of an official fix. When this does occur, the delay between initial disclosure and patch availability can result in defender fatigue. Temporary workarounds, which are often not as reliable as official patches, can also create a false sense of security. Additionally, temporary workarounds can often degrade functionality which limits deployment. This can create corresponding opportunities for threat actors, as demonstrated in the case of the ProxyNotShell vulnerability chain.

The two zero-day vulnerabilities that made up ProxyNotShell, CVE-2022-41040 and CVE-2022-41082, were discussed heavily in security reporting and media coverage. The vulnerabilities, targeting Microsoft Exchange, were named after the ProxyShell widespread exploitation campaign in 2021 due to the similarity in how ProxyNotShell also exploited Exchange servers. At the time of disclosure at the end of September 2022, Microsoft provided a temporary workaround, but did not release a patch. Microsoft released a patch for the vulnerabilities in early November 2022, more than a month after the initial disclosure and after media focus had subsided. However, security researchers continued to identify exploitation of the vulnerabilities, including in incidents reported in December that utilized a new ransomware called Play which circumvented the workaround published in September. The lag between disclosure and patch potentially contributed to many systems remaining unpatched months later. Moreover, because the earlier workarounds released at disclosure were consistently proven to be faulty, unpatched systems remained easy targets for threat actors.

Outlook

We expect that threat actors will continue to pursue the discovery and exploitation of zero-days, as these vulnerabilities provide significant tactical advantages in ease and success rates of exploitation, as well as stealth.

However, we anticipate that wider migration to cloud products could alter the expected trends due to differing patching and disclosure approaches. Cloud vendors can create patches and deploy them on behalf of customers, which greatly reduces patch times and therefore decreases risks of post-disclosure exploitation. However, many cloud vendors have historically chosen not to publicly disclose vulnerabilities in cloud products as reliably as other product types. This could affect zero-day disclosure counts as known to the public.

Implications for Defenders

As the vendors and products targeted by zero-days continue to diversify, organizations must efficiently and effectively prioritize patching to their specific circumstances to sufficiently mitigate risk. In addition to risk ratings, we suggest that organizations should analyze the following: types of actors targeting their specific geography or industry, common malware, frequent tactics, techniques, and procedures of malicious actors, and products used by an organization that provide the largest attack surfaces, all of which can inform resource allocation to mitigate risk.

Given that Microsoft, Google, and Apple continue to be the most exploited vendors, and that their presence is ubiquitous, proper configuration for these products is critical, including following best practices such as network segmentation and least privilege. But despite the prevalence of exploitation of the top three vendors, security teams must still weigh the risks from beyond those vendors and stay vigilant across their entire attack surface. Between 2021 and 2022, approximately 25–30% of zero-day vulnerabilities affected vendors beyond the top three and organizations must still allocate sufficient resources to defending these technologies.