The NHS is failing to fully exploit its national scale and heft to ensure patients receive cutting-edge treatments, according to leading health figures.

Concerns about the capacity of Britain’s health service to drive innovation have sharpened since global pharma giant Novartis recently scrapped a major trial of a new drug to reduce cholesterol.

The government has been anxious to trumpet life sciences as an area of strength following the UK’s departure from the EU but experts pointed to an array of hurdles, from the need to deal with multiple NHS bodies to funding constraints.

Some believe a conservative mindset among clinicians is also making it harder to bring novel treatments to patients.

Steve Bates, who heads the BioIndustry Association, a biotech sector lobby group, cited many examples of transformative drugs that had been successfully introduced into the NHS, from statins that combated cardiovascular disease to treatments for cystic fibrosis and rare diseases.

He also noted the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the public health body, produced assessments of the value of new treatments. “It’s not as if the NHS doesn’t have national guidance,” he said.

However, “what it seems to be resolutely resistant to is acting in a strategic and co-ordinated way on the adoption of innovation”, he said, pointing to the patchy take-up of Novartis’s inclisiran, which had varied considerably around the country.

Despite its size — the entire British population is covered by the NHS — the taxpayer-funded health service does not always commission and buy care as a single entity.

While some specialist services are commissioned centrally, in other instances companies wishing to penetrate the market have to negotiate with multiple local bodies.

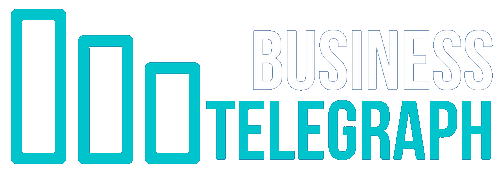

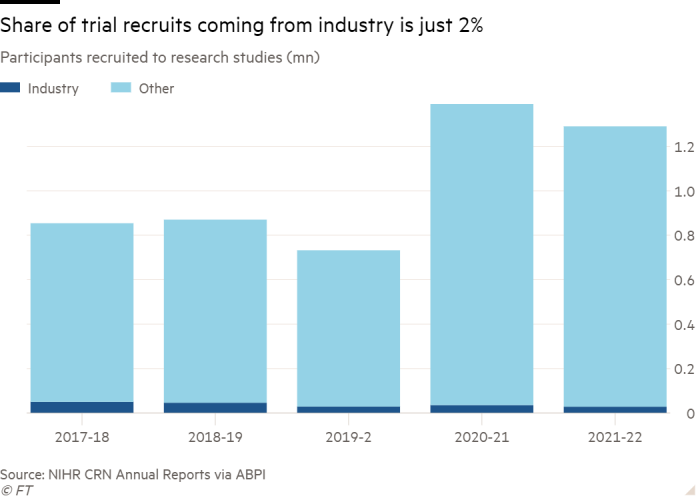

This atomisation also affects the UK’s ability to maintain or improve its share of clinical trials, which often give patients a final chance of a longer life, scientists suggest.

A forthcoming government-commissioned review is expected to conclude that trials are being hampered by sluggish hospital governance procedures and doctors lacking the time to enrol patients.

Martin Landray, the Oxford university professor who ran the landmark Covid “Recovery” trial, had been involved in the trial Novartis abandoned. He said that in Recovery, they worked closely with drugmakers Roche and Regeneron to the benefit of both companies and the patients.

However, he warned that the UK cannot “compete on the international stage” unless it addresses what is slowing clinical trials down, including having to sign contracts with hundreds of hospitals or trusts, rather than just one for the whole NHS.

His concerns are echoed by the pharma industry. Melanie Ivarsson, Moderna’s chief development officer, said Britain needed to cut bureaucracy to catch up with countries like the US. “It’s become very slow to start up trials in the UK, relative to other geographies.”

However, the NHS’s cradle-to-grave patient records remain a strong lure for companies such as Moderna.

The Covid-19 vaccine-maker is building an Oxfordshire campus that Ivarsson said would make Britain its “second home” for research. It is working with Protas, a non-profit run by Landray which specialises in large, late-stage trials.

“Where the NHS brings enormous value is that it is a closed healthcare system so that people are contactable, you can follow people’s health records long term,” she said.

Some, however, fear the culture of the health service can stymie innovation, a drawback compounded by its perennial funding problems.

John Bell, regius professor of medicine at Oxford, said: “The first thing everyone has to recognise is that the NHS is not a great place to adopt innovative products.”

He added that “big swaths” of Britain’s medical profession did not trust the pharma industry, unlike in other countries where it is seen as the source of the innovation that improves patients’ lives.

One of the criticisms that GPs levelled against inclisiran was that they were being expected to prescribe it without full information on safety and outcomes.

Margaret McCartney, a GP and freelance writer, said: “There is a big push in the government to have innovation. The problem for me is stuff that hasn’t been tested very well. It is the antithesis of evidence-based medicine.”

Despite the fate of the Novartis inclisiran trial, other partnerships are faring better. Grail, a company which has developed a blood test able to screen for cancer, is conducting a major trial with the first data on its performance expected next year.

The drive is being directed centrally by NHS England and does not depend on agreements with individual integrated care systems, which plan and commission health and care for their communities. The tests are carried out in mobile units rather than hospitals or GP surgeries.

Peter Johnson, NHS England national clinical director for cancer, said there was “very low risk to the NHS in an undertaking like this compared to the very big risk the company is taking on”. The company had enrolled 140,000 people, 70,000 of whom were having their blood tested “entirely at Grail’s expense”.

Other life sciences companies have found partners to help them navigate the NHS and overcome its challenges. Gilead has worked with scientists at Accelerated Clinical Trials Ltd to develop a blood cancer treatment.

ACT employs a network of research nurses based at NHS hospitals who can accelerate trial enrolments, and has established a lab devoted to processing patient samples.

Charlie Craddock, professor of haemato-oncology at the University of Birmingham and a non-executive director at ACT, said drugmakers were “biting off their arm” to work with the organisation.

Roland Sinker, recently appointed by NHS England as an unpaid national director for research and innovation, said the goal was to “speed up innovations, with a focus on prevention, early detection and integrated medicine” in a way that “maintains all the strengths of the NHS but minimises any additional burden”.

To do this, closer relationships with life science companies would be needed, argued Sinker, who is also chief executive of Cambridge university Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

“Is the NHS going to reinvent itself in that way by itself? I think it will do this much more effectively with the partnerships that we’re talking about,” he added.

The NHS said it directly commissioned a range of services and treatments nationally “including by using our strength as a single-payer health system to negotiate commercial deals for cutting-edge NICE-approved treatments”.

It added that the National Institute for Health and Care Research, a government body, offered a service that guided industry through all stages of planning and delivery of clinical trials. Newly established “integrated care boards” would “provide a simpler set-up to navigate compared to the previous model”, it added.